What’s the biggest reason to work less?

It affects your ability to make decisions. What’s the biggest reason business fail to grow or go out of business? Read Execution or Bad Choices – Why Do Businesses Fail to discover.

If you’re a busy business leader, working more doesn’t carry and high ROI. Every business leader is looking for a return on investment, whether its from themselves, their people, the equipment or location they occupy.

We’ve already shared ideas on how willpower decreases your effectiveness in LIE #4 – Willpower is Always on Will-Call and Willpower Rules Your Performance.

In Jeff Sutherland’s Scrum: The Art of Doing Twice the Work in Half the Time  Sutherland shares two research stories to show how decision-making is impaired when subjects worked too long.

Sutherland shares two research stories to show how decision-making is impaired when subjects worked too long.

Why Parole or Not: A Sandwich

In April of 2011, Israeli researchers published research about decision making. Their paper, titled “Extraneous Factors in Judicial Decisions,” reviewed a thousand judicial rulings by eight Israeli judges who presided over two different parole boards. The vast majority of the decisions the judges looked at were requests for parole.

Using years of experience and wisdom, these judges make critical decisions affecting not only the lives of the prisoners and their victims but the well-being of the community as a whole. Each day they heard between fourteen and thirty-five cases.

If you were a prisoner, what was the biggest factor in whether you’d go free or not?

True remorse, perhaps? Your reformation and behavior in prison? The severity of your crime?

None of those, actually. It turns out what really mattered was how long it had been since the judge had had a sandwich.

The researchers looked at what time judges made decisions, whether clemency was granted, and how long it had been since the judges had had a snack.

If they’d just gotten to work, or back from a snack break, or back from lunch, they made favorable decisions more than 60 percent of the time. That rate dropped to nearly zero by the time of the next break.

Researchers discovered after a short break, judges came in with a more positive attitude and made more lenient decisions. They displayed more imagination and capacity to see that the world, and people, could change, could be different. But as they burned up their reserves of energy, they began to make more and more decisions that maintained the status quo.

If you asked these judges if they were certain they were making equally good decisions each time, they’d be offended. But numbers, and sandwiches, don’t lie.

Sutherland notes, “When we don’t have any energy reserves left, we’re prone to start making unsound decisions. This phenomenon has been labeled “ego depletion.” The idea is that making any choice involves an energy cost. It’s an odd sort of exhaustion—you don’t feel physically tired, but your capacity to make good decisions diminishes. What really changes is your self-control—your ability to be disciplined, thoughtful, and prescient.”

Ice Water Test

Another fascinating experiment shows how important self-control is. A group of researchers wanted to know how making decisions affects self-control. So they gathered for their psychological research a group of collegiate undergraduates. They had one set of them make a bunch of decisions.

Students were presented with different products and asked to choose which they preferred. They were told to think carefully because they’d be given a free gift at the end of the experiment, and their preferences would decide what they’d get. The other set of students had no decisions to make.

The questions asked were challenging such as:

- What kind of scented candle do you like—vanilla or almond?

- What kind of shampoo brand do you prefer?

- Do you like this kind of candy or that?

Then they were given the classic test of self-control: How long can you hold your hand in ice water?

Whatever resource is burned up by making decisions is also used up in self-regulation. The students who’d made all the product decisions simply couldn’t hold their hands in the icy water as long as the control group that had been spared the decisions.

There is a limited number of sound decisions you can make in any one day. As you make more and more, you erode your ability to regulate your own behavior. You start making mistakes—eventually, serious ones.

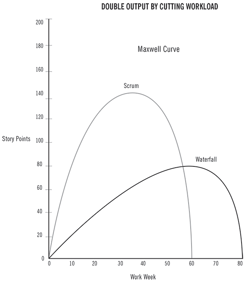

As the Maxwell Curve shows (see graph), those bad decisions impact productivity.

As the Maxwell Curve shows (see graph), those bad decisions impact productivity.

Sutherlands encourages, “So go home at five. Turn off the cell phone over the weekend. Watch a movie. Perhaps, most important, have a sandwich. By not working so much, you’ll get more and better work done.”

Scrum asks those who engage in it to break from the mind-set of measuring merely hours. Hours themselves represent a cost. Instead, measure output. Who cares how many hours someone worked on something? All that matters is how fast it’s delivered and how good it is.

A reminder from the Scrum TAKEAWAYS

Working Too Hard Only Makes More Work. Working long hours doesn’t get more done; it gets less done. Working too much results in fatigue, which leads to errors, which leads to having to fix the thing you just finished. Rather than work late or on the weekends, work weekdays only at a sustainable pace. And take a vacation. Don’t Be Unreasonable. Goals that are challenging are motivators; goals that are impossible are just depressing.

have you ever worked long hours to save a project? Do you have people in your organization who often ride in on a white horse (so to speak) to salvage a project, sales incentive, or challenging situation?

Next blog we’ll explore why if you need a hero to get things done, you have a problem.

.jpeg?width=150&height=135&name=Hand%20with%20marker%20writing%20the%20question%20Whats%20Next_%20(1).jpeg)