What Is the Most Promising Price Strategy to Pursue?

In Confessions of the Pricing Man: How Price Affects Everything Hermann Simon shares his thoughts on which of the price strategy options explored in his book: low, premium, or luxury is the most promising. His answer is not going to give you much comfort, “None of them is easy.” A company can become a tremendous success or a miserable failure with any of the three price positions.

In Confessions of the Pricing Man: How Price Affects Everything Hermann Simon shares his thoughts on which of the price strategy options explored in his book: low, premium, or luxury is the most promising. His answer is not going to give you much comfort, “None of them is easy.” A company can become a tremendous success or a miserable failure with any of the three price positions.

If you’re hoping this blog and Simon’s book offers an easy answer, I’m sorry.

Generally speaking there is no right or wrong strategy. Here are some of Simon’s thoughts on pricing. In a coming blog we’ll share Simon’s factors for each strategy pricing.

Premium Pricing

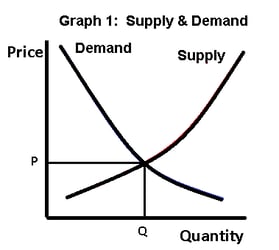

A premium price position moves the trade-off between cost and value to the forefront. A company needs to offer high-quality products. It still needs to ensure costs are in line. For premium and luxury goods, one needs to know whether such prestige effects exist and whether the demand curve has a part which slopes upward. If it does, the optimal price never lies in that portion of the demand curve. It always lies higher, in the part where the curve slopes downward again.  This reinforces a key lesson in this book: you need to know what your demand curve looks like, the more precisely, the better. When companies do not know their demand curves—especially in the case of premium and luxury goods—they will be poking around in the dark searching for the optimal price to charge.

This reinforces a key lesson in this book: you need to know what your demand curve looks like, the more precisely, the better. When companies do not know their demand curves—especially in the case of premium and luxury goods—they will be poking around in the dark searching for the optimal price to charge.

If some uncertainty remains, Simon recommends feeling your way along by gradually raising prices toward that higher range. It is also often wise—as the cases of Delvaux and Chivas Regal show—to combine the higher price positioning with an enhanced design or a packaging upgrade.

Price as an Indicator of Quality

An effect similar to the prestige phenomenon occurs when consumers use the price as an indicator of the product’s quality.

Many customers act according to the motto “you get what you pay for” and steer clear of low-priced products. But the flipside of that statement is also valid for many customers. For them, the simple equation “higher price = higher quality” becomes a handy rule of thumb. In such cases, a price increase can lead to higher unit sales

Low-Price Position

Success with a low-price position and especially an ultra-low price position requires the skills and abilities to keep costs as low as possible throughout the entire value chain. The corporate culture in those companies is often just as relentless and unforgiving as a luxury goods culture, but with the opposite focus. In contrast to the world of luxury goods, the culture of the low-price companies must be modest and frugal, if not outright stingy. This kind of working environment isn’t for everyone. But even in low and ultra-low price segments, a company needs sophisticated marketing know-how and needs to attract the right talent. Companies in these price segments must know precisely what they can leave out without causing the customer to refuse the product or switch to a competitor.

Simon offers that these brief thoughts suffice to show how difficult it is to execute both a high-price and a low-price strategy within the same company. The cultural requirements are radically different. Companies might overcome them if it can achieve a decentralized corporate structure. One company that pulls off that difficult trick is Swatch. One observer notes: “Swatch is well-positioned, because its brands range from inexpensive Swatch watches to the ultra-expensive Breguet and Blancpain lines.”

The Most Promising Price Strategy - Miracle Workers and Long Runners

Simon offers an answer to “what is the most promising price strategy?” from a more quantitative perspective.

Michael Raynor and Mumtaz Ahmed recently undertook that challenge, analyzing more than 25,000 companies which were listed on US stock exchanges between 1966 and 2010 and thus needed to make comprehensive financial data available publicly. Their measure of success is return on assets (ROA).

To make it into the top category, which the authors referred to as the “Miracle Workers,” a company needed to rank among the top 10 % in ROA in every single year it was publicly listed. Only 174 of the more than 25,000 companies, or 0.7 %, qualified.

The second category, the “Long Runners,” needed to be among the best 20–40 % performers in ROA in every single year. They found even fewer of these companies, a mere 170. The rest of the companies ended up in the category “Average Joe.”

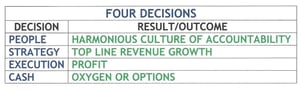

The authors then compared one Miracle Worker, one Long Runner, and one Average Joe from nine different industries. The research revealed two success guidelines, referred to as “better before cheaper” and “revenue before cost.”

“Miracle Workers compete on differentiators other than price and typically rely much more on gross margins than on lower costs for their profitability advantage,” the authors explained. “Long Runners are as likely to depend on a cost advantage as on a gross-margin advantage.” This reveals the share of companies which are successful with a premium price strategy is greater than the share of companies which have achieved sustained success with low-price strategies. Simon notes the business world has some extremely successful companies with low-price strategies, but they are few and far between. This must be simply because most markets have room for one and at the very most two successful “low price–high volume” companies.

Raynor and Ahmed note: “Very rarely is cost leadership a driver of superior profitability.” In contrast, most markets can support a larger number of premium-price companies who achieve sustained success. Simon believes Raynor and Ahmed’s research is both plausible and valid.

Low Price Sustainability

After 40 years in the pricing game Simon is convinced only very few companies achieve long-term success with a low-price strategy. “These companies must become very large and extremely cost competitive. Many more companies can achieve sustainable success with differentiated offerings and premium-price positions, but they will not grow to the size of the low-price contenders. For luxury goods we see again a relatively low number of successful companies, and they are the smallest of the three categories.”

In the 21st century, where single-digit margins are the norm, businesses must care about their pricing. Every percentage point change in prices can have a stunning impact on profitability. The lower your margins, the greater the need for caution. If a company has a margin of just 1% and wants to cut prices to grow market share, managers must realize that they are very likely to sacrifice all of their profits if they proceed.

Pursuing Profit

Simon’s views on profit is worth sharing. It’s so compelling I’m going to use his words from the book.

The pursuit of profit is both a driver of excellent pricing and an outcome of it; there is no way to separate the two topics. Profit is ultimately the only valid metric for guiding your company. The rationale is simple: profit is the only metric which takes both the revenue side and the cost side of a business into account. A company which wants to maximize its sales neglects the cost side. A company which wants to maximize its market share can distort its business in many ways. After all, the easiest way to maximize market share is to set one’s price at zero.

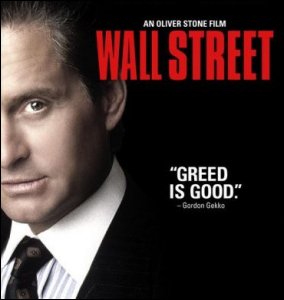

Simon adds to those that feel profit is bad, like it is often portrayed in Hollywood movies, “defending “profit” is not tantamount to defending greed and excess. It is a defense of corporate survival and growth.

Simon adds to those that feel profit is bad, like it is often portrayed in Hollywood movies, “defending “profit” is not tantamount to defending greed and excess. It is a defense of corporate survival and growth.

Let’s remember the comment by Peter Drucker, one of the most respected and widely followed management experts of our time: “Profit is a condition of survival. It is the cost of the future, the cost of staying in business.” German economist Erich Gutenberg remarked, “no business has ever died from turning a profit.”

Profit transcends other corporate goals because it ensures a company’s survival. Businesses cannot afford to treat profit as a “nice to have” or a “pleasant surprise” at the end of the year.

Employees need to understand this: if the company you work for makes no profit—or takes actions which puts profits in grave danger—your own job is at risk. It is only a matter of time before the cuts come.

Shall we explore some of the factors for premium and low price effective strategies? That’s our next blog.

.jpeg?width=150&height=135&name=Hand%20with%20marker%20writing%20the%20question%20Whats%20Next_%20(1).jpeg)