Prior to this blog series on Scrum our Strategic Discipline Blog dedicated a number of blogs to Gary Keller’s The ONE Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary Results. In the Final Lie to Achieving Our One Thing: Big Is Bad, we looked at how by fearing big success, you either avoid or sabotage your efforts to achieve it. Size is an issue if it limits your belief you can’t or won’t achieve what you desire.

Prior to this blog series on Scrum our Strategic Discipline Blog dedicated a number of blogs to Gary Keller’s The ONE Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary Results. In the Final Lie to Achieving Our One Thing: Big Is Bad, we looked at how by fearing big success, you either avoid or sabotage your efforts to achieve it. Size is an issue if it limits your belief you can’t or won’t achieve what you desire.

We discussed the dynamics of team versus individual performance Teams or Individuals – Scrum Lessons. The best teams perform two thousand times better than slow teams. This compares to an individual’s capacity to perform at a 10 to 1 ratio.

If you understand the implications of this, you should magnify focusing on team performance in your business.

There’s another important factor that determines team performance. It could be one of the elements diminishing your team’s productivity.

Size Does Matter, but Not the Way You Think

When Jeff Sutherland designed Scrum, he looked at what super-performing teams had that other teams didn’t. Why is it, Sutherland wondered, that some teams change the world, and others are mired in mediocrity?

What are the common elements that truly great teams have? Most importantly, Sutherland wanted to discover if he could reproduce them.

In Scrum: The Art of Doing Twice the Work in Half the Time  Jeff Sutherland notes on a Special Forces team, “everyone on this Scrum team has to know what everyone else is doing. All the work being done, the challenges faced, the progress made, has to be transparent to everyone else. And if the team gets too big, the ability of everyone to communicate clearly with everyone else, all the time, gets muddled. There are too many crosscurrents. Often, the team socially and functionally breaks into sub-teams that begin working at cross-purposes. The cross-functionality is lost. Meetings that took minutes now take hours. Don’t do it.

Jeff Sutherland notes on a Special Forces team, “everyone on this Scrum team has to know what everyone else is doing. All the work being done, the challenges faced, the progress made, has to be transparent to everyone else. And if the team gets too big, the ability of everyone to communicate clearly with everyone else, all the time, gets muddled. There are too many crosscurrents. Often, the team socially and functionally breaks into sub-teams that begin working at cross-purposes. The cross-functionality is lost. Meetings that took minutes now take hours. Don’t do it.

Sutherland’s point: Keep your teams small.

This requires a departure to the trend most business and sports teams gravitate toward. Specialization is the rage today; in Scrum you want cross-functionality.

Sutherland adds, “But just because cross-functionality can achieve great results, you shouldn’t play Noah and throw two of everything into a team. The team dynamic only works well in small teams. The classic formulation is seven people, plus or minus two, though I’ve seen teams as small as three function at a high level. What’s fascinating is that the data shows that if you have more than nine people on a team, their velocity actually slows down. That’s right. More resources make the team go slower.”

There’s a term In software development called “Brooks’s Law.” Fred Brooks coined the term in 1975 in The Mythical Man-Month. Brooks’s Law says “adding manpower to a late software project makes it later.”

Lawrence Putnam, a legendary figure in software development, made it his life’s work to study how long things take to make and why. He discovered projects with twenty or more people on them used more effort than those with five or fewer. And not just a little bit, but a lot!

A large team can take five times the number of hours that a small team would. It happened so frequently Putnam decided to do a broad-based study to determine what the right team size is. Putnam looked at 491 medium-size projects at hundreds of different companies. All projects required new products or features to be created, not a repurposing of old versions. Dividing the projects by team size Putnam noticed something immediately.

As teams grew larger than eight, they took dramatically longer to get things done. Groups made up of three to seven people required about 25 percent of the effort of groups of nine to twenty to get the same amount of work done. This result consistently recurred over hundreds and hundreds of projects. That very large groups do less seems to be an ironclad rule of human nature.

Why Larger Groups Take Longer to Get Things Done

In order to understand why a large group takes longer to complete a project you have to look at the limitations of the human brain. When I was in radio I recall hearing the classic George Miller study in 1956 showing that the maximum number of items the average person can retain in their short-term memory is seven. In fact if my memory serves me correct, at the time we learned it was 7 plus or minus 2. It may be the reason telephone numbers are seven numbers long is due to this research. Achieving success in radio is dependent upon your listener remembering your customer’s ad. It’s one reason we dissuaded advertisers from putting their phone number in the ad.

The problem with Miller’s work is that later research has proved him wrong.

In 2001, Nelson Cowan of the University of Missouri conducted a wide survey of all the new research on the topic. Cowan wanted to discover if the magic rule of seven was really true. Turns out the number of items one can retain in short-term memory isn’t seven. It’s actually four. The part of the mind that focuses—the conscious part—can only hold about four distinct items at once.

What does this mean to teams? It means there’s a hardwired limit to what our brain can hold at any one time. Back to “Brooks Law.” Brooks discovered two reasons why adding more people to a project made it take longer. The first is the time it takes to bring people up to speed: bringing a new person up to speed slows down everyone else. Reason #2 is not just how we think but with what our brains are capable of thinking. The number of communication channels increases dramatically with the number of people, and our brains just can’t handle it.

What does this mean to teams? It means there’s a hardwired limit to what our brain can hold at any one time. Back to “Brooks Law.” Brooks discovered two reasons why adding more people to a project made it take longer. The first is the time it takes to bring people up to speed: bringing a new person up to speed slows down everyone else. Reason #2 is not just how we think but with what our brains are capable of thinking. The number of communication channels increases dramatically with the number of people, and our brains just can’t handle it.

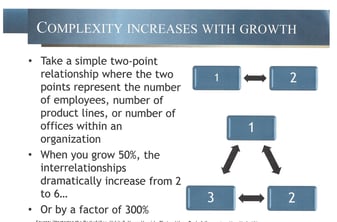

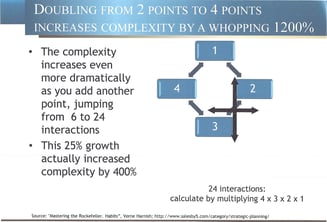

In our private and public workshops we used to share the complexity of adding people to an organization. The pictures here depict the increasing complexity and challenge as a company or in this case a team increases in size.

Calculate the Impact of Size

To calculate the impact of group size, take the number of people on a team, multiply by “that number minus one,” and divide by two.  Communication channels = n (n−1)/2. Tor example, if you have five people, you have ten channels. Six people, fifteen channels. Seven, twenty-one. Eight, twenty-eight. Nine, thirty-six. Ten, forty-five. Our brains simply can’t keep up with that many people at once. We don’t know what everyone is doing. The team slows down as members try to figure it out.

Communication channels = n (n−1)/2. Tor example, if you have five people, you have ten channels. Six people, fifteen channels. Seven, twenty-one. Eight, twenty-eight. Nine, thirty-six. Ten, forty-five. Our brains simply can’t keep up with that many people at once. We don’t know what everyone is doing. The team slows down as members try to figure it out.

Sutherland’s development of Scrum studied great teams. Why did Toyota refuse to take GM’s advice in their partnership and not keep the managers at the plant they acquired to build Toyota’s? Instead Toyota kept the employees GM recommended firing. We’ll look at the outcome of Toyota’s decision, next blog.

.jpeg?width=150&height=135&name=Hand%20with%20marker%20writing%20the%20question%20Whats%20Next_%20(1).jpeg)