Rarely in my 35 years of coaching and owning businesses have I seen it profitable to discount your prices.

Rare exceptions are when you have too much or old inventory tying up capital that could be invested in more profitable and fast moving goods. Occasionally competitive pressures demand lowering prices. In Confessions of the Pricing Man: How Price Affects Everything Hermann Simon agrees discounting is detrimental to profits and rarely returns an increase in market share.

Rare exceptions are when you have too much or old inventory tying up capital that could be invested in more profitable and fast moving goods. Occasionally competitive pressures demand lowering prices. In Confessions of the Pricing Man: How Price Affects Everything Hermann Simon agrees discounting is detrimental to profits and rarely returns an increase in market share.

COST of DISCOUNTING

In Price Is the Most Effective Profit Driver we previewed this blog with this question:

If you cut prices by 20%, how many power tools would you need to sell to achieve the same level of profit before the price cut?

The most common quick answer from managers is “20%.” If only it were that simple. Getting 20% is far below the volume you would need.

Even if your sales force succeeds in selling 20% more power tools after the price cut, you are still losing money. The contributions from your sales are not sufficient to cover your fixed costs. When your price goes from $100 to $80, you cut your contribution margin in half because it still costs you $60 to make each tool. The hard truth is that you need to double your volume after the price cut to keep your profits at the same amount. Anything less will reduce your profits.

The calculations above are rather simple. Yet many managers are startled to learn that a 20% increase in volume —which sounds like a success—would have catastrophic consequences for your bottom line.

Simon shares a story about a gardener (small business owner who showed an iron-clad grasp of prices and profits. This same understanding seems to elude manager's at large companies. He told the gardener if he gave him a discount of 3%, he would pay the entire bill immediately. “No way,” said the gardener with calm self-assurance. Surprised and curious, He asked why. “My net profit margin is about 6 %,” he said. “If you pay me immediately, that will obviously help my cash flow. But if I give you that 3% discount, I’ll need to hire twice as many people and do twice as much work to make the same amount of money. That’s why I can’t agree to your offer.”

Simon rarely sees managers and executives explain a price decision so succinctly and so correctly. Simon notes, “Perhaps that understanding comes from the fact that those dollars are all his.”

FREE SHIPPING ON SOCKS

Volume discounts and free shipping are common incentives for online businesses. A study by Simon-Kucher & Partners showed that consumers list “free shipping” as one of their main reasons for shopping certain categories online instead of going to the store. These incentives may indeed appeal to us as customers. But they can have an insidious effect on the company’s ability to earn money.

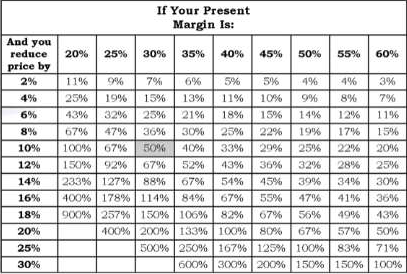

Let’s look at a company that sells socks online. If you order ten pairs, they will give you 20% off your purchase price. When Simon asked one of their executives whether that makes sense, he said that he marks up the socks by 100% from the wholesale price, so he can afford to offer customers that incentive. As an added sweetener, he also waived the shipping costs ($5.90) if you ordered more than $75 worth of socks.  The chart on the right shows the consequences of discounting depending on your gross margin and the volume required to make up the discounting to achieve the same profit.

The chart on the right shows the consequences of discounting depending on your gross margin and the volume required to make up the discounting to achieve the same profit.

Simon observes, “The decision to offer the discount and the free shipping cuts the sock seller’s profits by 51.8% compared to the base scenario in which he offers no discounts and charges for shipping. Now you argue that the volume numbers should be higher in the scenario in the right-hand column, because of the intrinsic appeal of discounts and free shipping. You’re right. How much higher must the volume be to achieve the same profit as without discounts?”

To achieve the same amount of profit, the sock seller would need to more than double his volume in the “discount and free shipping” scenario. He needs to sell 107% more pairs of socks.

Simon shares why it’s highly unlikely. First, consumer products such as socks are not so sensitive to price changes. Second, this kind of discount often leads to what consumer goods companies refer to as the “pantry effect.” People will stock up on socks solely to get the discount and the free shipping, which results in fewer orders in the future. These discounts train customers, even the most loyal ones, to buy only when there is a deal or in a way that gives them a discount. In this case, most will order ten pairs of socks to get the discount and free shipping. But they will not buy more.

Big numbers make great stories. If the sock seller’s volume was 50 or 60% higher in the “discount and free shipping” scenario, he’d probably be very happy.

The problem? Big numbers are not enough. You need gigantic numbers for these schemes to pay off, sometimes impossibly gigantic one.

The obsessive pursuit of the wrong goals—customer counts, revenue, and market share —leads even the sharpest managers to neglect the effects that discounts and promotions have on profits. It is hard to determine how many of the customers these promotions draw in will become repeat buyers at regular prices.

The simplicity and elegance of what Simon’s gardener knew is this: when you grant customers appealing and addictive goodies in the form of discounts, rebates, tax-free shopping days, free shipping, and on and on, you typically see increases in interest, traffic, sales volume, and most of the time (but not always) revenue. That is what makes these discounts so alluring and so tempting. They look like successes. But that success is often only an illusion.

GM – Employee Discounts for Everyone

Simon offers this example on this illusion and why it’s never a good idea to offer discounts in hopes to increase sales and gain market share.

Simon offers this example on this illusion and why it’s never a good idea to offer discounts in hopes to increase sales and gain market share.

The marketing teams at GM came up with a revolutionary idea. Instead of offering discounts or cashback incentives. They’d offer vehicles at the deep discounts reserved for employees. Starting on June 1, 2005, General Motors ran this promotion four months. Instead of quantifying the discount, it declared “GM’s employee price is what a dealer actually pays for a vehicle.”

What happened in the next two months?

This unprecedented marketing action yielded a volume increase so instantaneous and so large that it may have even taken GM and its dealers by surprise. In June alone, GM sold 41.4% more cars than it did in June 2004. In July, sales increased by another 19.8%, forcing GM to worry that it may literally run out of vehicles to sell. Ford and Chrysler launched their own radical versions of the employee discount program in July, which started to siphon off some of the attention and the demand.

ILLUSION OF SUCCESS

The first important question after two tremendous sales months is this: Where did those customers come from? Aside from a house or a college education, a new car is probably one of the biggest purchases consumers ever make in their lives. It is not a casual spur of the moment decision. We are not talking about pantry loading for socks or potato chips.

Almost all of those customers came from one place: the future.

GM extended the promotion through the end of September, even though sales began to plunge in August. Sales fell by 23.9 % in September and by 22.7% year on year in October; growth remained negative for the remainder of the year.

Instead of generating additional demand, GM borrowed customers from its future sales and sold those people cars at deep discounts

The second important question is the following: How much did all this cost? GM’s average discount per vehicle came to $3,623 in 2005. The company posted a loss of $10.5 billion.

One year later, GM Chairman Bob Lutz offered his view of the program: “We’re getting out of the junk business, like employee pricing sales that boost market share but destroy residual values. It’s better to sell fewer cars at higher margins than more cars at lower margins. Selling five million vehicles at zero profit isn’t as good a proposition as selling four million vehicles at a profit.”

Simon critically observed, “This is absolutely correct, but one wonders why clever Bob Lutz realized it so late. General Motors led the world in car sales for 77 consecutive years, starting in 1931. It fell to second place in 2008. The company filed for Chap. 11 bankruptcy in June 2009.”

Next blog we’ll explore: What Is the Most Promising Price Strategy to Pursue?

.jpeg?width=150&height=135&name=Hand%20with%20marker%20writing%20the%20question%20Whats%20Next_%20(1).jpeg)