Somewhere in your office probably lies an Operating Manual and List of policies for your company. If you have a documented version, you can probably blow the dust off of it, because it rarely or never is referred to except by your human resources department. If it’s a digital version it’s probably not been updated in some time.

A 1982 study “An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change” discovered what may seem like most organizations making rational choices based on deliberate decision-making is actually not the case. Instead firms are guided by long-held organizational habit patterns emerging from employees independent decisions.

These habits have more profound impacts than anyone previously understood.

The Power of Habit  provides two examples of how these employees’ decision-making led to crisis: First at a hospital and then at King’s Cross, London’s version of a subway station.

provides two examples of how these employees’ decision-making led to crisis: First at a hospital and then at King’s Cross, London’s version of a subway station.

At Rhode Island hospital the book provides a brutal display of how independent decisions can have catastrophic effects on employee morale and customer’s health outcomes.

Pray your hospital does not have the corrosive culture Rhode Island Hospital had in the early 2000’s.

“Some doctors were fine, and some were monsters,” one nurse who worked at Rhode Island Hospital in the mid-2000s told author Charles Duhigg.  “We called it the glass factory, because it felt like everything could crash down at any minute.”

“We called it the glass factory, because it felt like everything could crash down at any minute.”

To deal with tensions, the staff had developed informal rules—habits unique to the institution—that helped avert the most obvious conflicts. Nurses, for instance, always double-checked the orders of error-prone physicians and quietly made sure that correct doses were entered; they took extra time to write clearly on patients’ charts, lest a hasty surgeon make the wrong cut. One nurse told author Charles Duhigg they developed a system of color codes to warn one another. “We put doctors’ names in different colors on the whiteboards,” she said. “Blue meant ‘nice,’ red meant ‘jerk,’ and black meant, ‘whatever you do, don’t contradict them or they’ll take your head off.’ ”

One of the “black ink” doctors worked on an 86 year old man who arrived at the hospital with head trauma.

Because the doctor couldn’t get to the patient immediately due to a spinal surgery he was in the middle of, he decided to begin cutting a the skull of the man before it was verified which side to operate on to speed the process up. Despite the nurses attempting to follow the prescribed checklist, warning the doctor the consent form didn’t indicate where the hematoma was.

“I saw the scans before,” the surgeon said. “It was the right side of the head. If we don’t do this quickly he’s gonna die.”

One of the nurses requested they pull the films up again.

“We don’t have time,” the surgeon said. “They told me he’s crashing. We’ve got to relieve the pressure.”

The nurse requested they find the family.

“If that’s what you want, then call the f$#@%xg ER and find the family! In the meantime, I’m going to save his life.” The surgeon grabbed the paperwork, scribbled “right” on the consent form, and initialed it.

“There,” he said, “We have to operate immediately.”

The unwritten rule in this scenario at Rhode Island Hospital was clear: The surgeon always wins.

The skull was shaved; a drill broke through his skull, and then a saw cut out a triangular piece of the man’s skull.

“Oh my God,” someone said. There was no hematoma. They’d operated on the wrong side of his head.

The skull section was replaced; they turned the patient and performed the same procedure on the other side of his head. This time they found the hematoma. The surgery which should have taken an hour took twice as long.

The patient was taken to intensive care, never regained consciousness and died two weeks later.

Four months after the elderly man with the botched skull surgery died at Rhode Island Hospital, another surgeon at the hospital committed a similar error, operating on the wrong section of another patient’s head. The state’s health department reprimanded the facility and fined it $50,000. Eighteen months later, a surgeon operated on the wrong part of a child’s mouth during a cleft palate surgery. Five months after that, a surgeon operated on a patient’s wrong finger. Ten months after that, a drill bit was left inside a man’s head. For these transgressions, the hospital was fined another $450,000.

The fire at King’s Cross included the same type of independent decision making which killed 31 people. Poor communication, indeed failure to report the fire due to the unwritten rules and tightly prescribed chain of command by which the underground communicated with other departments, meant a lit match seen by passengers as a smoldering fire under the escalator went unreported.

The fire at King’s Cross included the same type of independent decision making which killed 31 people. Poor communication, indeed failure to report the fire due to the unwritten rules and tightly prescribed chain of command by which the underground communicated with other departments, meant a lit match seen by passengers as a smoldering fire under the escalator went unreported.

One of these unwritten rules handed down from employee to employee was they should never, under any circumstances; refer out loud to anything inside a station as a “fire”, lest commuter’s become panicked. Things simply weren’t done this way.

Complicating matters were issues with the London Fire Brigade. Despite written complaints to the Undergrounds Operations Director by the Fire Brigades Chief, the safety inspector for the Underground never saw this complaint letter. It was sent to a different division from the one he worked for. No one inside Kings Cross understood how to use the escalator sprinkler system, nor were they authorized to use the extinguisher. Another department controlled them. Indeed the Underground safety inspector forgot the sprinkler system even existed. It took a half hour before the first fireman even arrived at Kings Cross and by then the fire was already spreading and about to explode.

Unwritten rules in this situation and Rhode Island Hospital took precedence over any operating manual or policy.

The question from all of this: How many unwritten policies, routines and habits are your people following?

How many of these independent decisions are inhibiting and preventing progress in your business?

Habits can be good or bad. Is it time to develop habits and routines that deliver growth and improve communication in your business?

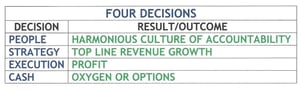

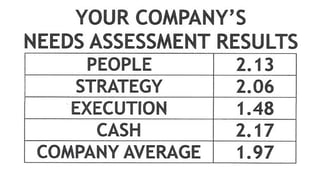

To learn better habits and train your people how to effectively communicate and make better decisions, plan to attend Mastering the Rockefeller Habits Four Decision Workshop. Download the Mastering the Rockefeller Habits Four Decision Workshop flyer. Register to attend this event November 12th in Cedar Rapids.

.jpeg?width=150&height=135&name=Hand%20with%20marker%20writing%20the%20question%20Whats%20Next_%20(1).jpeg)