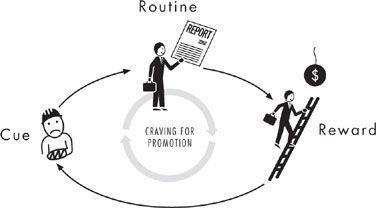

Habits can be a curse or a benefit.

Cues to form a Keystone Habit or habit loop like Paul O’Neill achieved at Alcoa can multiply benefits derived from the Keystone Habit. The value of one pattern change emerges in other areas providing multiplying leverage throughout an organization.

Recall how in Alcoa’s Key to Safety Success: Communication & Keystone Habit, O’Neill required Alcoa vice presidents to report an injury from an accident within twenty-four hours. Vice presidents are in constant communication with floor managers. Floor managers get workers to raise warnings immediately upon seeing a problem. They keep lists of suggestions nearby. When the vice president asks for a plan, he can dip into an idea box full of possibilities.

Remember the reward or incentive:

The only people who got promoted were those who embraced the system!

The only people who got promoted were those who embraced the system!

The trigger is the accident that gets the habit loop moving.

How did this transform the culture and increase Alcoa’s efficiency and productivity?

Six months after O’Neill became CEO of Alcoa, he got a telephone call in the middle of the night. A plant manager in Arizona was on the line, panicked, talking about how an extrusion press had stopped operating and one of the workers—a young man who had joined the company a few weeks earlier, eager for the job because it offered health care for his pregnant wife—had tried a repair. He had jumped over a yellow safety wall surrounding the press and walked across the pit. There a piece of aluminum had jammed into the hinge on a swinging six-foot arm. The young man pulled on the aluminum scrap, removing it. The machine was fixed. Behind him, the arm restarted its arc, swinging toward his head. When it hit, the arm crushed his skull. He was killed instantly.

O’Neill ordered all the plant’s executives—as well as Alcoa’s top officers in Pittsburgh—into an emergency meeting just fourteen hours later. They painstakingly re-created the accident with diagrams. They watched videotapes again and again. Dozens of errors had contributed to the death: two managers saw the man jump over the barrier yet failed to stop him; a training program failed to emphasize to the man that he wouldn’t be blamed for a breakdown; there were lacking instructions to inform him to find a manager before attempting a repair; finally the absence of sensors to automatically shut down the machine when someone stepped into the pit.

“We killed this man,” a grim-faced O’Neill told the group. “It’s my failure of leadership. I caused his death. And it’s the failure of all of you in the chain of command.”

The Power of Habit describes the scene: The executives in the room were taken aback. Sure, a tragic accident had occurred, but tragic accidents were part of life at Alcoa. It was a huge company with employees who handled red-hot metal and dangerous machines. “Paul had come in as an outsider, and there was a lot of skepticism when he talked about safety,” said Bill O’rourke, a top executive. “We figured it would last a few weeks, and then he would start focusing on something else. But that meeting really shook everyone up. He was serious about this stuff, serious enough that he would stay up nights worrying about some employee he’d never met. That’s when things started to change.”

The outcome of the accident is significant. Within a week of that meeting, all the safety railings at Alcoa’s plants were repainted bright yellow. New policies are written. Managers tell employees not to be afraid to suggest proactive maintenance. Rules are clarified so no one would attempt unsafe repairs. The newfound vigilance results in a short-term, noticeable decline in the injury rate. Alcoa experiences a small win.

O’Neil sent a memo that made its way through the entire company, “I want to congratulate everyone for bringing down the number of accidents, even just for two weeks.”

“We shouldn’t celebrate because we’ve followed the rules, or brought down a number. We should celebrate because we are saving lives.”

The reaction was overwhelming. Workers made copies of the note and taped it to their lockers. Someone painted a mural of O’Neill on one of the walls of a smelting plant with a quote from the memo inscribed underneath. O’Neill’s efforts began snowballing into changes that were unrelated to safety, but transformative nonetheless.

“I said to the hourly workers, ‘If your management doesn’t follow up on safety issues, then call me at home, here’s my number,’ ” O’Neill told author Charles Duhigg. “Workers started calling, but they didn’t want to talk about accidents. They wanted to talk about all these other great ideas.”

Many of the ideas provided dramatic impact. For example:

The Alcoa plant that manufactured aluminum siding for houses had been struggling for years because executives would try to anticipate popular colors. Inevitably their guesses were wrong. Consultants were paid millions of dollars to choose shades of paint. Six months later, the warehouse would be overflowing with “sunburst yellow” and out of suddenly in-demand “hunter green.” One day, a low-level employee made a suggestion that quickly worked its way to the general manager: If they grouped all the painting machines together, they could switch out the pigments faster and become more nimble in responding to shifts in customer demand.

Within a year profits on aluminum siding had doubled.

“It turns out this guy had been suggesting this painting idea for a decade, but hadn’t told anyone in management,” an Alcoa executive revealed. “Then he figures, since we keep on asking for safety recommendations, why not tell them about this other idea? It was like he gave us the winning lottery numbers.”

The small wins from O’Neill’s focus on safety created a climate in which all kinds of new ideas bubbled up.

As Alcoa’s safety patterns shifted, other aspects of the company started changing with startling speed, as well. Rules that unions had spent decades opposing—such as measuring the productivity of individual workers—were suddenly embraced, because such measurements helped everyone figure out when part of the manufacturing process was getting out of whack, posing a safety risk. Policies that managers had long resisted—such as giving workers autonomy to shut down a production line when the pace became overwhelming—were now welcomed, because that was the best way to stop injuries before they occurred.

As Alcoa’s safety patterns shifted, other aspects of the company started changing with startling speed, as well. Rules that unions had spent decades opposing—such as measuring the productivity of individual workers—were suddenly embraced, because such measurements helped everyone figure out when part of the manufacturing process was getting out of whack, posing a safety risk. Policies that managers had long resisted—such as giving workers autonomy to shut down a production line when the pace became overwhelming—were now welcomed, because that was the best way to stop injuries before they occurred.

O’Neill never promised that his focus on worker safety would increase Alcoa’s profits. However, as his new routines moved through the organization, costs came down, quality went up, and productivity skyrocketed. If molten metal was injuring workers when it splashed, then the pouring system was redesigned, which led to fewer injuries. It also saved money because Alcoa lost less raw materials in spills. If a machine kept breaking down, it was replaced, which meant there was less risk of a broken gear snagging an employee’s arm. It also meant higher quality products because, as Alcoa discovered, equipment malfunctions were a chief cause of subpar aluminum.

What’s your One Thing? What cue can you set up to begin a positive habit loop in your company?

Many of your company’s best ideas may be trapped inside the minds of your people on the ground floor of your business. Are you missing the opportunities they can provide? Can one focus, one priority, inspire your employees to willing communicate with you and your managers to revolutionize your business?

How can you get previously tardy, disgruntled workers to perform consistently and predictably? Several companies including Starbucks and the Container Store have discovered how to give their employees willpower, dramatically improving performance and employee engagement. That’s next blog.

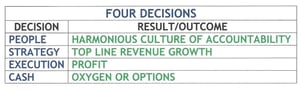

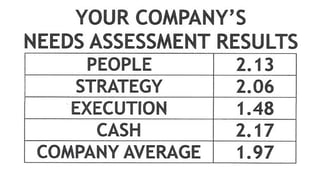

If you’d like to learn more about these best practices and apply them to your business, including the meeting rhythms habit, the impact of One Thing priority, how to do effective annual and quarterly planning, then plan to attend Positioning Systems Mastering the Rockefeller Habits Four Decision Workshop. Download the Mastering the Rockefeller Habits Four Decision Workshop flyer. Register to attend this event November 12th in Cedar Rapids.

.jpeg?width=150&height=135&name=Hand%20with%20marker%20writing%20the%20question%20Whats%20Next_%20(1).jpeg)